Disturbing Trends in Automation: Two Steps Forward, Three Steps Back?

“Do you think God stays in Heaven because he too lives in fear of what he’s created?”

—Spy Kids 2

What’s the speed limit? If you’re a Tesla, you think it’s 85. Now does that make you want to get behind the wheel of one and engage its so-called autopilot function? This is no laughing matter. People are dead because these flawed features have been both over-sold and rushed to market.

One case involved a driver who, against the owner’s manual recommendations, was possibly watching a movie on a portable DVD player while their car sped down a highway, and its cameras failed to distinguish an oncoming truck from the sky, resulting in that passenger’s death. Another fatal crash took place with a jaywalker, and the autonomous vehicle involved was programmed in such a way as to only allow for the possibility that people walk across a street at intersections (to quote the NTSB report, “The system design did not include a consideration for jaywalking pedestrians”).

There’s no innate common sense to a piece of software, which merely behaves exactly how you tell it to. So if you only build in hard and fast rules, for instance a directive that it cannot cross a solid white line, you end up with a car that can be trapped in the middle of the road by someone chalking a circle around it.

These hijinks are interesting, because we’re also seeing people deliberately tipping over service robots and engage in other behaviors that show a resistance towards automating tasks that humans have traditionally performed. This phenomenon goes back at least as far as the industrial revolution. When faced with one’s own obsolescence, in the light of newer methods and technological advances in particular, we have a tendency to rebel against that sort of progress.

New processes will hardly ever be perfect, but that’s not what we’re after. We should want to make overall improvements without being needlessly encumbered by established practices. It is inevitable that, just as a machine can nowadays lay railroad spikes faster than any human possibly could, one day the average error and casualty rates for entrusting a piece of software to drive cars will be lower than that of relying upon humans to manually operate the same vehicles.

There are a few fascinating ramifications to this. Does your self-driving car, for example, supposing it has to crash into something, steer for a motorcycle or a truck? If it’s looking to optimally protect itself and its inhabitants, above all other concerns, the answer is the motorcycle, because even though that’s more likely to cause injury to the other vehicle’s occupant, hitting the truck could be, even if nominally so, a worse consequence for you. Yikes.

Safety measures programmed into vehicles on the road today aren’t quite ready for truly autonomous driving. Errors with them happen regularly enough that a human still needs to be behind the wheel in case they’re needed to take control. We don’t want something similar to how the pilots who weren’t properly trained on how to override a dysfunctional anti-stall feature of the Boeing 737 MAX, killing everyone on board as a result.

Thinking again of that self-driving car trapped by the white line drawn around it, machines appear to have a failure of imagination. This is a limitation that our species certainly shares when it comes to allocating for the range of human behaviors which occur due to individual differences.

Many of the Web’s failures, if you think back to the promises of its early days, are due to some unforeseen vulnerabilities from trolls, vandals, scammers, and whatnot. Remember how the “nofollow” specification was supposed to end spam? The creators of the Internet never fathomed how their inventions would be corrupted by the prevalence of dark patterns, conspiracy bubbles, and algorithmic bias that we see today.

This is especially true with regard to how the likes of Facebook and YouTube cater to and thereby promote the spread of bigotry and misinformation. The problem is that Twitter doesn’t know Pizzagate didn’t actually happen. It’s akin to the dumb Tesla; it needs a human to take the wheel by in this case manually banning those sorts of claims, and that’s at best a questionable stopgap in our pursuit of knowledge.

I’m in the process of helping to set up an updated interface for our main search engine at work. Many of my colleagues have approached configuring this new library discovery layer by simply attempting to replicate every aspect of the old platform. I’m all for not needlessly breaking continuity with the past, but a lot of these custom settings are based on what seem to be unfalsifiable beliefs about how librarians want non-librarians to use a library. It’s as if we cannot conceive that anyone, library degree holder or not, would want to do things differently.

We need to stop sabotaging the future. Barring evidence to the contrary, leaving configuration options on their default settings, which may very well constitute an overall improvement to accessibility, is a far more sustainable approach. At some point, we don’t have the human power to keep up with sweating the small stuff by tinkering around after every little change anyway.

Anyone who has had to load ten thousand e-book records, with whatever vendor-supplied metadata they come with, can attest to the pros and cons of such situations. In the case of a computer assigning subject headings to books, employing automated solutions can be cutting corners a bit too much.

Considering again how that Tesla (and “dumb” was perhaps a misnomer, as that ascribes to it a degree of intelligence, whereas these things really are devoid of anything resembling what could at a minimum be called human intelligence) didn’t know that jaywalkers could exist: it’s clear that there’s room for improvement in setting the appropriate ground rules for how we let computers think for us. This is also of crucial importance because there’s ways in which we don’t actually want them to think like us, as well as instances where they don’t really think like us at all.

There’s a slew of examples demonstrating this. One program was charged with building a fast robot, and it came up with an ultra-tall design that would simply fall over, thus quickly traversing a long distance, because doing so met the parameters of its design criteria. Another piece of image recognition software misidentified a husky as a wolf, not because of any characteristics of the dog, but due to the snow in the background of the photograph, since that was more often associated with known pictures of wolves.

Then there’s some less amusing ways in which prejudice has been propagated by artificial agents—such as with predictive policing programs and in other areas, where data corrupted by disparities from human biases is used to teach computers, essentially, to practice discrimination themselves.

This is obviously not a good thing. We should know better. “Unsafe at any speed” applies to such a practice, and it remains to be seen if we can ever have a computer smart enough to filter out those irrational thought patterns which are exceedingly implicit in our everyday lives.

I’ve personally experienced this, as I’m sure we all have, in one way or another. During what was supposed to be a routine physical, to make a long story short, the nurse did not want to shave my chest for an EKG, producing abnormal results, and the doctor sent me to the ER in an ambulance because they thought I might be having a heart attack, even though the paramedics confirmed I wasn’t. Compare that case of overtreatment with the story of a library school classmate of mine, who entered a hospital with chest pains, proclaiming to be having a heart attack, only to be told, ‘It’s just stress, go home.’ She is fine now, but she did have a heart attack at the time.

I know that’s just two anecdotal cases, but iterations of this discrepancy have happened millions of times, whether it’s picnicking while black or what have you. It’s enough to be overwhelming. Everyone therefore needs to do a better job at combating any unfair treatment witnessed being carried out, not to mention whatever unjust tendencies we observe and acknowledge within ourselves, as well as not passing on all forms of blind hate to our descendants, whether they be biological offspring or what might one day become an artificial life form.

It still sounds like something out of science fiction, but computers are, news flash, getting more powerful. We could very well have librarian robots someday, and I don’t want them to be a product of sloppy programming, where, say, they’re given a primary command to, “Preserve and defend the collections by any means necessary,” resulting in them running amok and killing any patrons who scuff up books. Or think of a robot in a hospital who, as far as it can tell, successfully puts an end to any patient’s discomfort by deliberately terminating their life.

That’s a stretch. The documented biases in results from library discovery layers, however, are already here. In my experience, moreover, the flaws in these products with their abilities to provide connections between different data sources are also growing:

This chart shows one of the more exhausting things I deal with. It’s the pronounced rise of problems, as reported by library users, regarding how a supposedly grand unified research tool actually delivers results from all of our various content providers. Last week, the Collection Management team and I took in 35 of these reports. By way of comparison, our organization’s LibAnswers system recorded 15 total tickets during the same time period.

Discovery layers do a lot of heavy lifting. They’re better and more accomplished by leaps and bounds than their predecessors. Yet in this case, it shows how there’s also more that can go wrong, and why we seem to be losing the battle in our efforts to make things easier to use.

Here’s one of the latest defective records we’ve had reported. It’s an article from 2019 that shows up in a search for full-text articles because one of our Ebsco databases claims to have current coverage of the journal. “E-Pub Ahead of Print” items, however, are not included, so the only way for us to get this article (expanded definitions of “Fair Use” notwithstanding) is to shell out $45 for it on the publisher’s site. Not exactly platinum open access.

Licensing and managing electronic resources for an academic library is a tricky business. The absurdity of NFTs has got nothing on the broken system that is the scholarly publishing industry. Like our current Covid situation, it didn’t need to be this way. And my loathing of those responsible for that fact is something quite hard to swallow.

As any long-distance runner could tell you, finding the proper pace when you’re in for a long haul is fraught with challenges. You have to strike the right balance between a multitude of factors. That is why it doesn’t help any when you have a computer that wants you to go 85 when 35 is actually optimal, because starting off too fast can ruin your race.

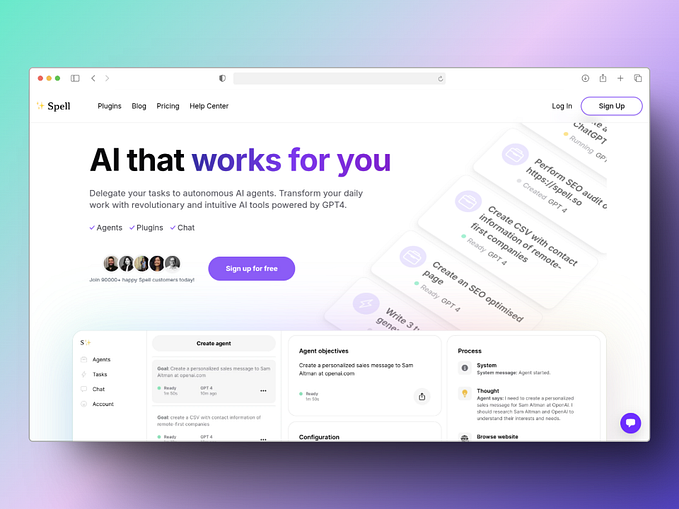

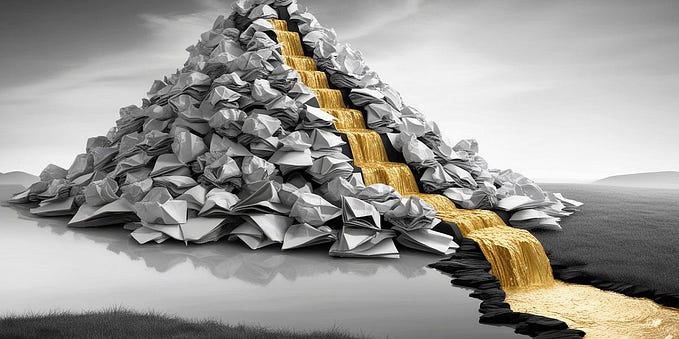

In the past few years we’ve witnessed rapid and dazzling advances in the sort of technologies which have turned a few individuals into billionaires. Other areas, conversely, seem to be all the more lacking.

As someone in the public sector, working for a non-profit, I look at all those graphs of CEO pay and generational wealth, consider how I’m effectively making less than I did over a decade ago, and can’t help but wonder at how unbalanced our society has become based on what we treat as important when measured by where our efforts are focused.

There’s no easy answers to all of this. Trusting in the free market to give people what they want is how you end up with the rise of fake news, while doing something like letting librarians vote on how a search engine should be developed gets you the clusterfuck that is the UI of library discovery systems. Maybe we do need strong AI to, if nothing else, save us from ourselves.